Why agility?

Organisational agility is increasingly critical for the survival of organisations in turbulent environments. Organisations are looking for ways to increase their capacity to deal with a fast-changing environment with all its fluctuations in demand, risks and opportunities.

Lucy Loh & Patrick Hoverstadt, Directors, Fractal Consulting

Patrick Hoverstadt spoke at IRM UK’s Business Change & Transformation Conference Europe 18-20 March 2019 on the subjects, “Patterns of Strategy” and “Organisational Agility Beyond the Hype: What it is, How You Get It and How to Measure It.”

The next IRM UK Business Change and Transformation Conference Europe will take place from 16-18 March 2020, London

Truly a VUCA world, then: volatile, uncertain, complex and ambiguous. One which is adding to the variety and complexity of activities which the organisation needs to handle, one which is increasing the possible futures they need to prepare for, and the speed at which they must do so, in order to survive and thrive in their environment. But as Deming wrote: “You don’t need to change – your survival is not mandatory.” And in response, we would say:

To survive, change at least as fast as your environment.

(And, ideally, faster than your competitors too)

Pressure to deliver today creates a push for efficiency, a push to lock in resource to doing more of the same thing. But pressure to be ready for tomorrow needs freedom of choice and manoeuvre, ability to break out of today’s ways of thinking and doing to do something different. And this needs enough spare resource to effect change: agility. It’s important to be clear on the agility ‘requirement’ – how much agility do you need? where? how quickly?

Without knowing how fast the environment is changing, it’s impossible to know the minimum rate of change the organisation requires. Without knowing how agile an organisation is, it’s not possible to know what strategies are possible, whether managers can manage (effect change) or whether the organisation is likely to survive, in the context of the agility required to survive and thrive in its environment. So, agility matters: it matters strategically and it matters operationally, and therefore it matters to be able to design organisations with requisite agility.

Agility in practice

Organisational agility isn’t just an abstract idea – we define agility as the ability to redirect resources in a timely way, faster than the changes in the organisation’s environment and faster than the rate of change by competitors. This requires situational awareness (ability to sense and make sense of the environment), coupled with swift ways to reach decisions and

then enact them. Agility comes with a price tag – it means having resource in readiness or easily withdrawn from other non-mission-critical activities incurs an overhead. Its value comes when the organisation can rapidly redesign and reconfigure capabilities to achieve a desired position in its environment.

There are two elements to agility. Operational agility is about being able to re-deploy resources quickly to absorb fluctuations in demand. Strategic agility is about being able to quickly re-deploy resources onto new areas of business. Both are about re-deployment, only the intent is different – one short term and operational, the other to seize a strategic opportunity or respond to a strategic threat. It’s much more than having ‘spare’ resource, as the resource needs to be capable of doing the required work, and quickly. But an agile organisation doesn’t just happen. It’s important to have a clear view of where you want and need stability and where agility is important. Efficiency can be the enemy of agility, as it reduces both the resource available and the ‘gene pool’ necessary for innovation.

Developing organisational agility

Fractal uses a model of organisational agility that has been developed from two main sources: Stafford Beer’s Viable System Model (VSM) and John Boyd’s OODA loop. These map onto one another and mirror each other but each has different strengths and weaknesses and a different emphasis. VSM was developed as an approach to understanding what organisations need to be able to adapt to a changing environment so they can maintain their ability to survive. OODA (Observe, Orientate, Decide, Act) was developed in the military as a way to understand how to think and act ahead of competitors in a fastpaced environment. Both are interested in how organisations need to think and redeploy resources to survive and thrive in turbulent environments and both have an excellent track record in doing that. OODA has been a cornerstone of military strategic thinking for decades and has been proven in both warfare and business environments. VSM has been used for decades and is able to predict with 71% confidence an organisation’s ability to avoid or survive organisational crises. Both share common characteristics and we have taken those as the basis of our work on organisational agility and on the measurement of agility.

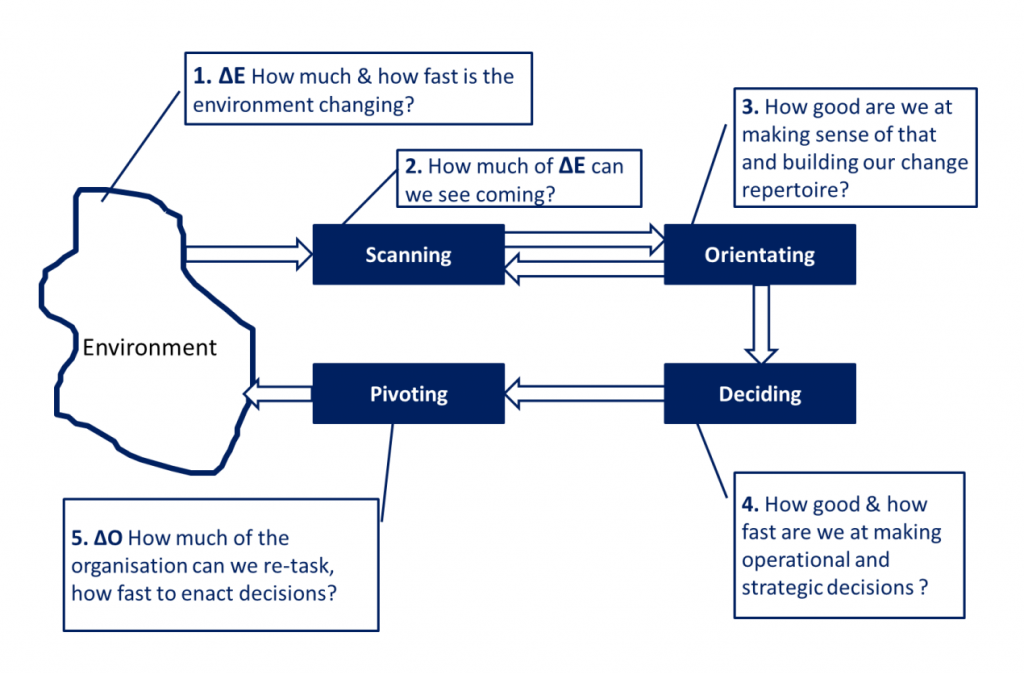

There are 5 basic components to the model and that we measure:

- The rate and scale of change in the organisation’s environment.

- Ability to scan for those changes.

- Ability to make sense of the information from scanning to input to decisions.

- Ability to make decisions.

- The rate and scale of change of the organisation that allows the organisation to survive and thrive in its changing environment.

Measuring organisational agility

Given the criticality of agility both strategically and operationally, it is clearly important to be able to measure the level of agility which an organisation has, and the level of agility it needs. Any difference between the two then becomes an issue of organisation design or development: how to alter the organisation to give it the agility it needs while ensuring the agile resource retains sufficient alignment to short-term goals and longer-term strategy.

We cover each of the five areas in the figure above. Each has a description, an overview of things which we typically measure, and some examples of interventions which improve the agility of the relevant stage: its speed, completeness or quality.

1. Environmental change

The fundamental driver of the need for agility is how much and how fast the organisational environment is changing, so this assesses in broad terms the scale of background volatility of the environment and therefore how agile the organisation needs to be. Both operational and strategic delivery may need agility, and it’s crucial to have clarity on how much agility is required and where. So the rate and scale of change in the environment sets the context. And it is relative to this rate of change that the level of organisational agility needs to be measured. There is little point in benchmarking against organisations from other sectors since by definition they operate in different environments with different rates and scales of

change.

Measuring environmental change

We are interested in the rate at which the organisation is presented with threats and opportunities, and the scale of those. This sets the agility ‘bar’ which the organisation must be able to respond to.

2. Scanning

The rate of change in the organisation’s environment drives the need for agility, and scanning is the ability to scan the current and future environment to be able to understand the scale of the agility need. A key element of an organisation’s viability depends on its capability to look outside the organisation and into the future, and sense and make sense of what is there, so that the organisation can work out where, how much and how fast to adapt the organisation to maintain its fit with its environment. So, one aspect of environmental scanning is to inform decision making about options for change and adaptation.

Ideally, environmental scanning is a do-forever, do-all-the-time activity that sensitizes the organisation to what is important in its environment, so that more people can engage in looking, and factors relating to the environment and the future are more readily brought into decision taking, creating a healthy balance of inputs. Scanning isn’t a passive state of merely looking. It’s about actively exploring, actively seeking information and in particular actively seeking indicators or evidence that your current understanding is flawed or plain wrong. This isn’t common, though, as people tend to look for and give weight to information that confirms their assumptions and beliefs about the situation more than the information that tends to challenge them. Yet, of course, it’s the information that challenges your assumptions that helps you to update and improve your understanding of your environment, and so improve the appropriateness of your decisions.

Developing the organisation’s ability to detect changes in its strategic environment before they become critical is the easiest way to improve responsiveness: it provides a longer window to act or to react – it’s effectively a way to slow down time. When done on a continuous basis, scanning is relatively cheap and helps to better attune your organisation

to its environment.

Measuring scanning

Here we look for two key things. One is the quality and completeness of the scanning: is it sufficiently thorough, does it cover all the key facets of the environment, from drivers and trends to the actions of other relevant players? The other is the speed at which the findings, the information and intelligence, are reported back to the organisation. No point in an attentively detailed picture if it arrives too late for appropriate decision and action; scanning speed needs to be linked to the rate of change in the environment it is scanning.

1. Orientate

The heart of Orientate comprises two models: one is a model of the environment and the actors in it, and the other is a model of the capabilities of the organisation. This is based on the premise that the ability to manage in a given context depends on well the context is understood, which depends on how useful the models of the environment and the organisation are. Good models are highly valuable – think about “a picture is worth a thousand words.” Orientation is where information about external changes and internal capabilities gets integrated – is there the capability to exploit this opportunity or respond to that threat?

In both OODA & VSM the process of modelling to understand how the environment is changing is key – to capture and structure what you know about the situation. Orientation is about the structuring. And here are a couple of key points. The quality of your model of your environment and couplings determines what you can observe. With a poor model, you will be blind-sighted to even observe and notice some aspects of your environment. Even assuming that you can observe those aspects, the quality of your model determines how you will interpret or make sense of what you observe and what those observations actually mean. Once you’ve detected signals of change from the organisation’s environment, making sense of those is critical – does this trend represent a threat or an opportunity or a bit of both? How do you know how to interpret the moves by competitors or the market, or regulators? So Orientation shapes what you Scan, what you Decide and how you Pivot and is in turn shaped by the feedback from your interaction with your environment, the Scanning. It’s about looking at an opportunity or problem from multiple perspectives. In any environment and particularly in a competitive one, the more that you can keep your models of the environment (your Orientation) well aligned to that environment, the better your decision taking will be.

There is a feed through from Scanning: Scanning quality has a direct impact on the quality of the modelling in Orientation: low Scanning scores mean the information provided to Orientation is poor quality or missing altogether. And the quality of Orientation has a direct impact on the quality of the Scanning because Orientation indicates where Scanning should be taking place.

Measuring Orientate

Measurement for Orientate indicates the quality, completeness and use of models. Specifically, we look for the quality and completeness of two models, one of the organisation itself and one of its environment, and the integration between the two. Then we look for evidence that the models are actually being used, to build scenarios or otherwise to inform decisions. If the models are good but little used, or the models are poor but used regularly then Orientate will be weak: both parts need to be strong. And finally and as for Scanning, we look for the speed at which Orientation is done, drawing on the intelligence and information from the Scanning.

4. Decide

The faster you can take good decisions, the faster you can move to action, and speeding up the rate of decision-making is one of the easiest ways to improve agility because it usually requires fewer people to change their process and it is usually high leverage too. There’s often an assumption that better decisions take longer, but this isn’t the case if you design your decision making well. There are two main streams of decision taking, one operational/tactical and one strategic, and it’s important to separate them as there is usually a big difference between the decision making in these two areas. For each, there are two aspects to be measured and developed: first, speeding up the decision making process itself and second, getting the right informational feeds for decision-making (ie improving both Scanning and Orientation).

Measuring Decide

In Decide we’re interested in a number of things. First we measure the quality of the decision process. We’re also concerned with the forwards impact of Orientation: poor Orientation impacts Decide, just as poor Scanning impacts Orientation. We split out strategic and operational decisions, and for each we measure the decision taking ability and the decision taking speed. We also split for familiar and unfamiliar decisions – deciding about a familiar situation can be much faster than deciding in an unfamiliar one, so the balance between the two can be critical.

5. Pivot

Ultimately organisational agility involves the ability to switch resources so that the organisation can change direction quickly and this is true both in operations and strategically. At any time in an organisation, there will be a certain amount of resource, often the vast majority of the resource, committed to business-critical activities using set processes and ways of working. There will be some resource which can be moved onto change and transformation efforts with very little notice. There are two aspects to this, one is how much resource you can move from business as usual into a new direction and the other is about the relative degree of autonomy this resource has. The change resource needs to be given appropriate autonomy to do what is being asked of it: shackle it with the same constraints as the business-as-usual resource and little will be possible. You can see how Agile approaches in software are underpinned by both the ’switchability’ of resource and enhanced autonomy.

The speed of resource redeployment must be appropriate to the rate of change in the environment: if the organisation lags behind that change rate, it loses its strategic fit with its environment. Because being able to redeploy resources quickly can be expensive (relative to the business cost of improving scanning orientating and deciding) it’s critical to know what types of resources need to be mobilized and what autonomy they’ll need to be effective. As with decision making, this is assessed in terms of operational / tactical agility (how fast you can change the basic operations) and strategic (how fast you can change the organisation itself).

Measuring Pivot

The measurement for Pivot focus on how well and how quickly decisions can be put into action to change the direction of part of the organisation. First, we measure how well resource can be Pivoted, both operationally and strategically. And as for the previous stages, we measure how fast the organisation can enact the Pivot, both operationally and strategically, and use the resource to deliver the required actions and outcomes.

Agility

Agility is about effectiveness in these four interdependent areas: Scanning, Orientate, Decide and Pivot. In measurement terms, each must be good for the whole to be good. If you don’t Scan what is happening in your environment, and synthesise that into Orientation, how could you decide where and how to be agile? If your Decision processes are poor, then the impact of your agility effort will be reduced, and if your ability to Pivot your organisation is weak, then you aren’t actually able to be agile at all.

The fundamental driver of the need for agility is how much and how fast the organisation’s environment is changing, so we summarise our measurement by comparing the rate and scale of change in the environment with the available rate and scale of change by the organisation. That means looking at the ability to move through Scan-Orientate-Decide-Pivot in a timescale and to a scale which is appropriate for the environment.

And perhaps the last word could go to John Boyd. He saw that what mattered is having enough Orientation to know that what you are currently doing won’t be enough in the future, and then having the courage to leave a known and profitable fit while there is still time to change. The ultimate agility.

Agility and architecture

Architecture and architects have a huge potential role to play with regard to agility. There needs to be measurement of the rate of environmental change and the current state of agility in the organisation. There will most likely be a ‘delta’, a gap between the current agility and the agility requirement. That requirement needs to be very precise, not just a “be more agile”, but a “be this much more agile in this part of the organisation” and the architecture can support that definition work, in particular looking for any areas of the organisation subject to conflicting requirements: a need for stability and a need for agility. Once the agility requirement is clear, it then becomes an enterprise design and development task, and there are many different organisational interventions which can be used to build the required organisational agility.

Lucy Loh has worked as a consultant since 1996 in both public and private sector organisations and in a number of countries, supporting clients in strategy, organisation design and development, performance and change. She specialises in using systems approaches for analysing and designing organisations, and for development of strategy. She has written a number of research papers and speaks regularly at conferences. Lucy and Patrick Hoverstadt co-authored a book on a systemic approach to strategy – Patterns of Strategy.

Patrick Hoverstadt has worked as a consultant since 1995 with organisations in both the private and public sector across the world, mainly on strategy, organisational design and change. He specialises in using systems approaches for analysing and designing organisations and in working with very large complex organisations including whole sectors. He has developed methodologies for several difficult business problems. He has written numerous research papers, is a regular keynote speaker at conferences, has contributed to several books on systems, organisation and management, is the author of “Fractal Organisation” a book on organisation published by Wiley in 2008 and used on seven masters programmes around the world, and is co-author of “Patterns of Strategy” a book on a systemic approach to strategy published by Gower in 2017. He chairs SCiO the professional body for systems practitioners and is a Visiting Research Fellow at Cranfield School of Management.

Copyright Lucy Loh & Patrick Hoverstadt, Fractal Consulting