Enterprises make architectural investments, whether or not they have an architecture team. Yet, executives can often find it hard to put a value on those investments, or even know which ones they are. That’s usually because they are targeting and measuring innovations in the enterprise’s structure using goals that are about the performance of the existing structure. In the projects portfolio, the architectural investments end-up buried amongst all the non-architectural ones, and the value of having architects is misunderstood or lost.

Chris Potts, Independent Corporate Strategist Specializing in Enterprise Investment, chrisdpotts@dominicbarrow.com

Chris will be presenting the following course for IRM UK in London: Management Strategies for Enterprise Architecture 24-25 November 2016, London. Chris will also be chairing our launch event Innovation, Business Change & Technology Forum Europe 2017 taking place in London in 21-22 March 2017

It is essential that executives know which projects are architectural and which are not. While many projects, big and small, enhance the performance of the existing enterprise, architectural projects are redesigning its shape and structure. There is a vital creative tension between investing in the enterprise as it already is, or in what it must become. Put simply, architectural projects are driven by a different goal from all the non-architectural ones.

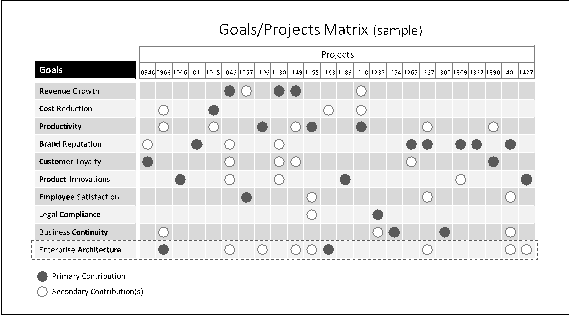

A portfolio of investments in change includes two kinds of architectural project. The first, and more obvious kind, is where a project’s primary contribution is architectural innovation. Less obvious are projects where the primary contribution is non-architectural (e.g. revenue growth, cost reduction, or compliance), but the project includes an architectural change. The following Goals/Projects Matrix illustrates these two kinds of architectural investment:

In an enterprise’s strategy for investing in change, differentiating each project’s primary contribution from any secondary contributions greatly increases the probability of the portfolio succeeding. Projects are difficult, and frequently fail to deliver their intended benefits. And, in principle, the more goals a project is promising to contribute to, the harder it will be to succeed. While no project has a 100% probability of success, the persistent benchmark is that, on average, 70% of projects fail. When things get tough, everyone needs to know which contribution is the most valuable, and which might have to be sacrificed.

With that in mind, what would be the impact on architectural investments, if the final row in the matrix above did not exist? Nobody would be able to see whether a project included an architectural change. Even those projects where architectural innovation was the primary reason for investment would be buried amongst all the others. In projects where architectural change was a secondary contribution, that could too-easily be sacrificed when things get tough. All the highly-valuable work of architects and others would probably be lost, and the enterprise would either randomly change its structure, or not at all.

So, let’s consider how the architects, portfolio managers and executives create and populate that final row, if it doesn’t already exist. What makes a project architectural – what are the defining features? For example, is it because an architect came up with the idea? Is it it because the change is big, in terms of scope, cost or risk? Or, perhaps, is it because it is regarded as a transformation?

Identifying which projects are truly architectural requires an architect’s unique skills and experience. An apparently identical change may be architectural in one enterprise, and not in another. None of the features described above are definitive, either way. Indeed, features such as who thought of a change, its size, and whether it is considered transformational, steer us away from noticing what makes a project truly architectural, because they are about the change itself, rather than the consequences of the change.

The reason we need architects is because changes can have architectural consequences, either desirable or not. Those changes, collectively, must continually be turning us into the enterprise we next need to be. They may be anyone’s idea, big or small, transformational or not. The architect’s eye for detail is instead focused on how the enterprise will be the same or different, architecturally, after each change is made.

How do enterprise architects know which changes will have architectural consequences, and share that knowledge with executives? They focus on the characteristics that define the enterprise’s architecture, and that executives find meaningful. These characteristics can be about the enterprise’s fundamental purpose (e.g. we are a hotels group), aesthetic coherency (e.g. do our app, website, hotels and service exhibit the same brand values), or measures of the enterprise’s structural performance (e.g. profits per room).

By focusing on architectural characteristics, executives and architects can agree what the enterprise next needs to achieve through architectural innovations, without yet knowing how. Then, they can ensure that the projects portfolio delivers the required architectural consequences, when they are needed, and as efficiently as possible. They can also ensure that no projects are taking the enterprise in a different architectural direction from the one they have agreed.

As the example of the Goals/Projects Matrix helps to illustrate, the visibility of architectural investments relies on the basic design of the projects portfolio. How projects are selected and managed has a big impact, too. Here are the five most significant aspects to check:

- The portfolio is driven by the enterprise’s goals for investing in change

- Achieving the enterprise’s agreed architecture is one of those goals

- The architects and executives are working with an agreed set of architectural characteristics

- In the process for selecting new projects, the architectural consequences are explicit, and agreed

- Project managers are accountable for the achieving the agreed architectural consequences of their projects

In any enterprise where the architectural investments are currently buried in-amongst all the others, the most valuable thing an architect can do is find and expose them. In the language of architects, those investments constitute the ‘as-is roadmap’. Once that roadmap is visible, executives, architects and portfolio managers can together determine the probability of it delivering the enterprise’s architectural ambitions. Then, they can decide what to do with the existing investments, and start planning for the the ones that come afterwards.

There is, occasionally, an unexpected twist in the tale. When it becomes clear what constitutes an architectural investment for a particular enterprise, the projects that executives thought were architectural can turn out not to be, after all. In that scenario, the buried treasure is the knowledge that, while the executives have ambitions for the future shape and structure of the enterprise, none of the existing investments will get them there. Were that to be true, then the value of having architects should be even more obvious.

Chris Potts is an independent corporate strategist specializing in Enterprise Investment – the powerful combination of Enterprise Architecture and Investment in Change. He is a mentor to executives, enterprise architects, and project portfolio managers. Chris is also a professional speaker, and the author of the world’s only trilogy of business novels, The FruITion Trilogy.

Copyright: Chris Potts, Dominic Barrow